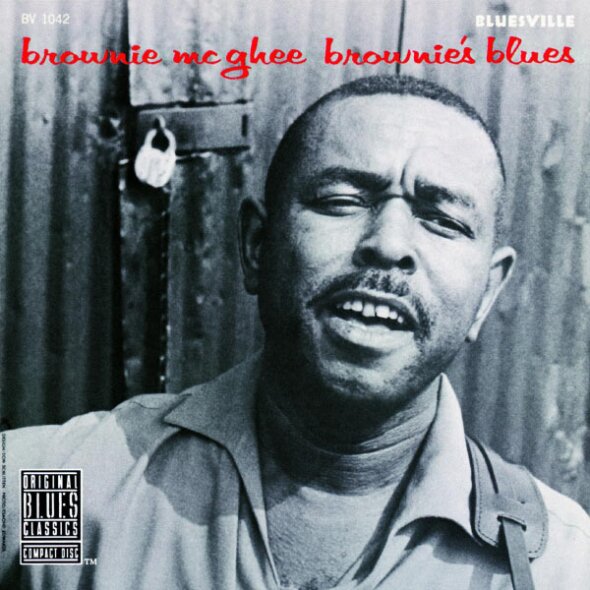

“I’ve been coming to Oakland for years. I used to come up here quite often to listen to the blues legend Brownie McGhee. We used to sit in his garage and eat candy. And talk—and talk some shit, really.”

So spoke Southern California-raised singer, songwriter, and slide guitar sorcerer Ben Harper when he last passed through The Town, playing The Fox Theater shortly after it reopened in 2009. Harper was back in the area last month, albeit in the North and South Bay, playing consecutive sold-out solo concerts, at Weill Hall on the campus of Sonoma State University and at Mountain Winery in Saratoga.

For the uninitiated, Ben Harper is a successful recording artist and touring musician who has crafted an expansive and eclectic career spanning two decades and countless genres. His music is born of and indebted to a blues-folk fusion, but runs the gamut from soul to gospel, rock to reggae, country to funk, with jazz and hip-hop principles never too far. In the late ’90s and early 2000s he quickly became a star overseas, headlining European festivals for audiences upwards of 25,000, but back home—as was the case with many black artists before him—his following was a fraction of the size. Nonetheless, his prolific creative output and his willingness to stretch out in new directions, while still staying reverent to his roots, kept his U.S. fan base strong, if smaller in stature than that of many other countries. It also hasn’t hurt that his live shows are long, raucous, spiritual affairs that foster a genuine connection with his audience, and feature the frequent special guest, dynamic covers, and incendiary reimaginings of his already vast catalogue.

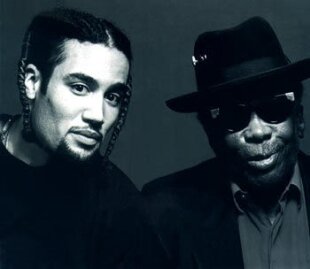

During 2012’s string of solo shows on the east coast (which concluded with his first headlining gig at New York City’s Carnegie Hall), Harper thrilled followers and casual fans alike with several extended, as-yet-unreleased lap slide guitar compositions, a couple ukulele adaptations of old classics, and the premier of a medley of Marvin Gaye’s Trouble Man and Pearl Jam’s Indifference on the vibraphone. The following year’s west-coast version of the tour (featuring a stop at Davies Symphony Hall in San Francisco) peaked when Memphis-reared, Chicago-fortified blues harmonica king Charlie Musselwhite joined him on stage to play a few scorching cuts from their new collaborative record.

Suffice it to say, as concertgoers entered the recently built Weill Hall—a gorgeous building modeled after the Boston Symphony Orchestra’s summer home at Tanglewood , featuring a wall that opens up onto a landscaped lawn—the air was abuzz. With the crowd welcoming him in rousing applause, Harper took his seat below a replica marquee of his family’s famed music store and launched into a brand new, Delta blues dirge entitled Call It What It Is (Murder), in which he decried the recent police killings of unarmed black men, invoking the names and stolen lives of Trayvon Martin, Ezell Ford, and Michael Brown. Over a brooding slide riff that deftly conjured the slave songs of the American South, Harper intoned bleakly and deliberately: “They shot him in the back / ’Cause it’s a crime to be black / So don’t act surprised / When it gets vandalized / Call it what it is / Call it what it is / Call it what it is / Murder!” The tune not only summoned up images of the ongoing protests in Fergusson, Missouri, but also called to mind past instances in which Harper’s music similarly denounced flagrant purveyors of racist violence, be it the LAPD in the time of Rodney King or the Bush administration during and after Katrina.

After that tone-setting opener, which it’s safe to say floored quite a few, Harper moved into more familiar terrain, playing decade-old crowd-pleasers Better Way and Diamonds On The Inside, the former performed with a looped tabla sample and his signature teardrop-shaped Weissenborn—a fretless, hollow-bodied lap slide guitar built largely of Hawaiian Koa wood back in the 1910s and ’20s. He then dipped back even further, giving renewed life to songs such as Please Me Like You Want To and Excuse Me Mr., both from his second album, 1995’s Fight For Your Mind. His poignant lyrics were sung in the understated hushed tones he grew known for over his first few years as a touring artist as well as in the more far-reaching falsetto he sharpened after getting a few albums under his belt. His ability to intimately grapple with his past, oppression, love lost, and self-conception, kept his audience enraptured.

But it wasn’t all stark and solemn. Harper frequently joked with the crowd between songs, poking particular fun at his status as an anomaly in the music business, mostly on the basis of his non-linear body of work. He mentioned that Pharrell had called and asked for his hat back, then put things in their proper historical context: “In all fairness, I’ve been wearing Borsalinos since…” After playing an unadorned version of With My Own Two Hands, a song celebrating individual people’s capacity to effect change, which first appeared on record as a more elaborate roots reggae number, he mentioned the flak he gets about it from “pessimists.” And without missing a beat: “They can kiss my ass every day—morning, noon, and night! I wouldn’t sing it if I didn’t believe it.”

Harper proved slightly less talkative the following evening, performing at Mountain Winery’s stunning outdoor amphitheater in Saratoga shortly after the sun went down. He opened the gathering with four songs he hadn’t included the night before, among them the infrequently played By My Side and There Will Be A Light, evidence of his commitment to keeping each concert a fresh experience. And while the set ambled about a bit less cohesively than that from the Sonoma State gig, it benefited not only from the surreal, serene environs of a castle-resembling venue on a South Bay mountaintop at summer’s end, but also from the guest appearance of Harper’s mother. She came out, as she had the night prior, to play a few of the new tracks from their parent-child project Childhood Home. The song Farmer’s Daughter seemed to spark the audience’s greatest emotion, with its tale of modern agricultural exploitation backed by banjo and Dobro: “We can’t plant /And we can’t grow / We can’t reap / And we can’t sow / Don’t own the seed / Can’t plant our rows / It all belongs to Monsanto”).

A further highlight was Harper’s crowd-thrilling cover of Prince’s Purple Rain, sung with minimalist, at times percussive-style playing of the Weissenborn, and segued into unexpectedly from another rarity of his early recording career, the somber Give A Man A Home.

Harper also praised The Bay at length, comparing Oakland, San Francisco, and Santa Cruz to France, where he saw his quickest, and arguably greatest, popularity as an artist. He named Northern California “a home for the music I make” and “the first place that spoke English” to accept him, allowing the belief that “America might just understand what I’m doing.” This love affair with The Bay has been well-documented, as he’s often discussed the area’s support, and reminisced on early, decisive experiences here, be it during well-over-capacity shows at The Warfield in San Francisco, historic gigs at The Greek in Berkeley with guests like Santana and Maceo Parker sitting in, or an unforgettably elegant couple of nights at The Paramount in Oakland.

Ben Harper performing “Where Could I Go?” live at The Paramount Theater in Oakland, CA

As I drove back up the 880 to The Town beneath a glowing half-moon, my mind wandered towards Harper’s 2009 mention of his tutelage under the aforementioned bluesman Brownie McGhee 20 years ago. What sorts of candy did the two of them crunch on? What kind of shit did they talk? And could the aging McGhee, a towering figure of Appalachian music turned Oakland transplant and local hero, have ever imagined his then-unknown pupil building on the history lessons imparted in that garage to carve out a genre-defying niche just as he himself had years earlier?

For fans of Ben Harper, his formative experiences learning at the feet of blues and roots greats is the stuff of legend. Taj Mahal, a frequent visitor to The Folk Music Center in Claremont, California, founded by Harper’s maternal grandparents in the 1950s and kept in the family ever since, gave him his first touring gig in 1993. That same year, John Lee Hooker got hold of a promo copy of Harper’s first full-length album, Welcome To The Cruel World, and invited the newbie to fill an opening act slot for a handful of shows he was playing at The Sweetwater Saloon in Mill Valley. It’s there that the two laid the foundation for a mentor-mentee relationship that would last the remaining decade of Hooker’s life. It’s also where Harper first met Musselwhite, with whom he would collaborate on a long-discussed, generations-bridging album a decade-and-a-half down the line (last year’s Get Up!, released on the renowned Stax label, which nabbed the Grammy for best blues record of 2013).

For fans of Ben Harper, his formative experiences learning at the feet of blues and roots greats is the stuff of legend. Taj Mahal, a frequent visitor to The Folk Music Center in Claremont, California, founded by Harper’s maternal grandparents in the 1950s and kept in the family ever since, gave him his first touring gig in 1993. That same year, John Lee Hooker got hold of a promo copy of Harper’s first full-length album, Welcome To The Cruel World, and invited the newbie to fill an opening act slot for a handful of shows he was playing at The Sweetwater Saloon in Mill Valley. It’s there that the two laid the foundation for a mentor-mentee relationship that would last the remaining decade of Hooker’s life. It’s also where Harper first met Musselwhite, with whom he would collaborate on a long-discussed, generations-bridging album a decade-and-a-half down the line (last year’s Get Up!, released on the renowned Stax label, which nabbed the Grammy for best blues record of 2013).

All the same, Harper’s mention of an informal apprenticeship with Brownie McGhee—who’s credited with exposing the finger-picking Piedmont blues guitar style of the Carolinas to an international audience during the form’s 1960s revival—was a biographical nugget about which even the most ardent of Harper fans were likely unaware. McGhee moved to Oakland in 1974, living in what he called “The House That Blues Built,” at 43rd and MLK, which garnered official landmark status from the city shortly after his passing in the mid ’90s, and which some sources actually suggest McGhee constructed himself.

While McGhee was most celebrated for championing a highly syncopated acoustic guitar aesthetic that predated the Chicago electric blues boom, he also experimented broadly with his sound, cutting a number of R&B-sowing “jump” records with “his Jook House Rockers” in the late 1940s and ’50s, which prominently featured up-tempo piano and saxophone playing. And while “East Coast Piedmont blues is decidedly an African American art form”—to quote a research project at UNC Ashville influenced by Samuel Charters’ 1977 text Sweet As The Showers Of The Rain—an amalgamation of influence is undeniable, including “ragtime, country string bands, [and] traveling medicine shows … blend[ing] both black and white, rural and urban elements.” This willingness and ability to traverse styles no doubt influenced Harper as he studied with McGhee in that old North Oakland garage.

While McGhee was most celebrated for championing a highly syncopated acoustic guitar aesthetic that predated the Chicago electric blues boom, he also experimented broadly with his sound, cutting a number of R&B-sowing “jump” records with “his Jook House Rockers” in the late 1940s and ’50s, which prominently featured up-tempo piano and saxophone playing. And while “East Coast Piedmont blues is decidedly an African American art form”—to quote a research project at UNC Ashville influenced by Samuel Charters’ 1977 text Sweet As The Showers Of The Rain—an amalgamation of influence is undeniable, including “ragtime, country string bands, [and] traveling medicine shows … blend[ing] both black and white, rural and urban elements.” This willingness and ability to traverse styles no doubt influenced Harper as he studied with McGhee in that old North Oakland garage.

It speaks, as so many stories do, to The Town’s, and The Bay Area’s, significant, if consistently under-recognized, role in the lives and careers of some of the nation’s most intriguing musicians. As if on cue, a few weeks after the Sonoma and Saratoga shows, Harper officially announced he’d be reconvening his band of 15 years, The Innocent Criminals, following a half-decade hiatus, and kicking things off with a four-night run at The Fillmore next March. Why? Harper said, “It felt like the right place for us to set sail.”

To check out more of my work, please check out raphaelcohen.net