The documentary Til Infinity opens with a subtle f-bomb aimed at any and every record label. The voice is that of Del The Funky Homosapien. It’s a voicemail recording he left on Q-Tip’s answering machine in the early 90’s. On that same voicemail, Del brags about this group he’s been working with out of East Oakland, a group called Souls Of Mischief.

The documentary Til Infinity opens with a subtle f-bomb aimed at any and every record label. The voice is that of Del The Funky Homosapien. It’s a voicemail recording he left on Q-Tip’s answering machine in the early 90’s. On that same voicemail, Del brags about this group he’s been working with out of East Oakland, a group called Souls Of Mischief.

That same recording was sampled on the promo tape to the group’s first project, filmmaker Shomari Smith said during a recent phone interview.

“At that time, when groups were introduced to the world, rappers were associated with other rappers,” said Smith. “For example,” Smith continued, “Del was introduced a few years before by his cousin, Ice Cube.”

Smith, who says that he intended his film to capture the feel of Fall ’93, concluded his statement by saying, “I wanted to show what Hip-Hop was like back then. Folks who remember being introduced to (Souls Of Mischief) back then– they will know that quote.”

Who could foresee that a group of boys rapping on a corner on 82nd ave in East Oakland would earn a landmark deal with Jive Records, which allowed them to retain the rights to their music; and twenty years later, their anti-record label approach would prove to be a successful business model.

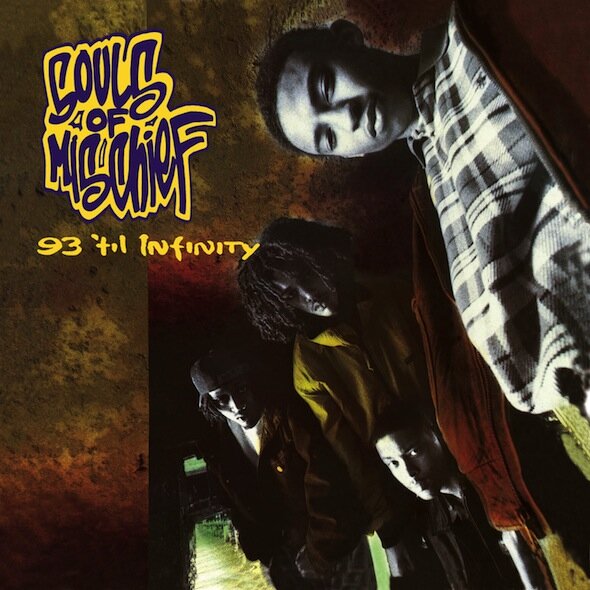

The Hieroglyphics crew is a group of rappers, producers and DJ’s. One of smaller collectives out of the Hiero crew is known as “Souls Of Mischief”. Within the Souls of Mischief there are four men: A +, Opio, Phesto and Tajai. These four men have been riding together since well before 1993. But on September 6th of ’93, they dropped an album that shook the industry.

“We hailin from East Oakland, California and, um

Sometimes it gets a little hectic out there

But right now, yo, we gonna up you on how we just chill…”

With those opening words to the track “From 93′ til”, Tajai’s teenage voice was inscribed in the Hip-Hop textbook.

The documentary dives into chapter “93 til”, and explores the world of Souls of Mischief.

Shomari Smith, who grew up with the members of Souls of Mischief, says that their friendship was one of the three factors that inspired him to make this movie. The other two reasons being that he has worked on short documentaries before, therefore he has the technical know-how. And finally, he loves Hip-Hop.

Director, Shomari Smith

The director shows the widespread impact of the Hiero crew through interviews with notable Hip-Hop names, such as Murs, members of Slum Village, and Snoop Dogg.

The interview with Redman was the best. Reggie “Redman” Noble, a top selling artist in the early 90’s, told a personal account of losing one of his most important fans to the Souls Of Mischief back in 1993. He lamented over the fact that his sister was ecstatic when Souls Of Mischief dropped their first album, and she wouldn’t pay his music a lick of attention. While maintaining his jokingly-serious “fuck you” attitude, Redman charismatically and sincerely ended his interview by giving the Hiero crew love and respect.

The tone of the film was full of love and respect–from the interview with Shock G at the start, the sit down with Thembisa Mshaka in the middle, and the clip of Questlove at the very end of the movie.

The interviews with the members of Souls carries a feeling of nostalgia. The men take a journey to their old neighborhood, and even to the corner where they’d meet up as youngsters. The photos of Phesto, the fashion guru, sporting the flyest gear of the time, coupled with the image of Opio’s and A+’s hairdos worked together to create a wild vision of what 1993 in Northern California looked like. But nothing worked as well as Tajai’s sit-down interview. He took us on a trip down memory lane, complete with references to sleepovers and jealousy behind who owned the vibrating football field toy.

The time period and the music merged when they mentioned the machinery they made their music on. Tape decks. Sound boards. Amps. Sampling machines. No computers. No MP3s. No downloads.

This was the late eighties and early 90’s in East Oakland. Instead of getting involved in the dope game, making music is what these young men did after they got out of class at Skyline High School.

Phesto and his baby

“It reflected in the music on the album,” said the film’s director when asked about the environment of East Oakland during that time period. “They talked about what it was like to be a young person in Oakland at that time,” said Smith. During the elementary and middle school years, (mid 80’s) Smith says that the group saw Oakland change. “Businesses were closing. Drug culture was taking over,” Smith said as he looked back on that period. “We saw a lot of thriving neighborhoods decay in a way that we hadn’t seen,” he added. “It really did affect where we hung out and the things we did; and it showed in the music they made.”

The true life accounts mixed into the music and caused many “everyday people” to gravitate toward their tunes. The Souls Of Mischief sound wasn’t the hustler’s anthem of E-40, nor the soundtrack to a pimp’s life like Too $hort’s music; it wasn’t even the fight against the system sound that Boots Riley and the Coup had. But because Souls of Mischief hailed from the same area as all the aforementioned artists, those elements were present, just not as blatant.

Souls of Mischief were just a little more chill. Their style drew comparisons to A Tribe Called Quest, Slum Village, and even Outkast. But Souls of Mischief was from the West Coast. And they’d quickly let you know.

The one major downfall to the two-hour documentary film: it’s too chill. There is no conflict. There is no massive falling out. There is no shooting. No baby-mama drama. No mention of jail time or anything that goes into the traditional rap story. Just a lot of reminiscing and good jokes. (Again, the interview with Redman is the best thing).

When asked what he wanted to tell the world about this project, Shomari Smith said, “it’s a way for the guys to tell their own story. In their own words. About a really incredible work in Hip-Hop history. When we’re all gone, that story can still be around somewhere. And it’s told by the guys who did it. First hand.”

Smith, who was enrolled in art school on September 6th 1993, says he cut class to buy the tape from Leopold’s in Berkeley. He remembers it clearly. “Listening to that album does take me back to that time,” said Smith. “I was an Illustration major in college. I had a pullout stereo, It had a handle– you pull it out of the car so no one steals it. You probably don’t remember that!” He laughed and continued, “thinking about that now, it was the greatest thing at the time: I was in school and I had a new album to listen to in my Mazda hatchback.”

Smith concluded with saying that he’d really like to stress to young people the importance of understanding their time and era. “Every time period has it’s importance. For me, it was a coming of age time,” said Smith. Smith continued to say that he wants the people who come after he did, and the people who came before he did, to understand; and for those who lived it to remember.

“You’re not just listening to music, you’re a part of something,” said Smith.

The films next screening is set for the end of September at Stanford University; the event will be in collaboration with Adisa Banjoko and the Hip-Hop Chess Federation. Date TBD.

The films next screening is set for the end of September at Stanford University; the event will be in collaboration with Adisa Banjoko and the Hip-Hop Chess Federation. Date TBD.

For more information, check www.tilinfinitydoc.com.